SLOW

YURI and KAORI

character development

By Heera Alaya

March 27th, 2024

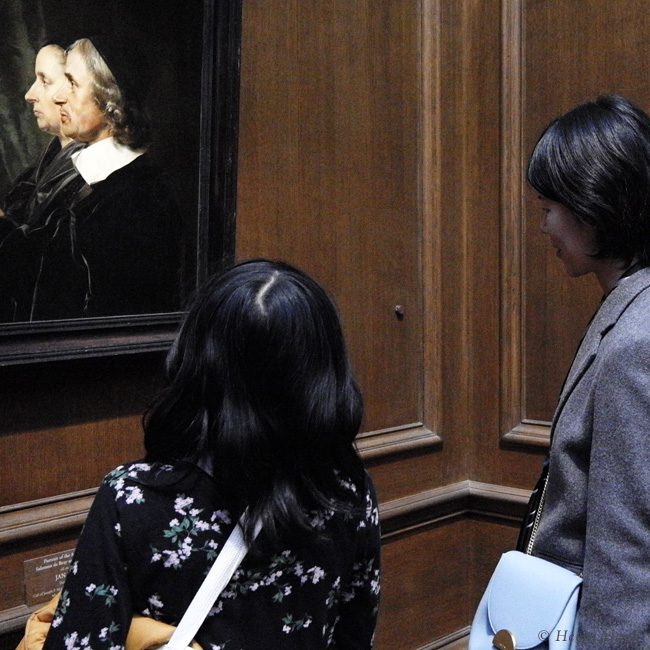

A world-class canvas for treasured canvasses, the National Gallery of Art [NGA], Washington, D.C., United States, is more than a physical space—it is a living canvas showcasing art, culture and education. Viewing the artworks—paintings and sculptures—compels me to acknowledge the crucial role of the museum guardians. Where would these masterpieces reside without their meticulous curation, protection and illumination? What would we know of history? And how could we learn about ourselves?

Every aspect of this institution’s [NGA] canvas results from a machinery of highly detailed planning—from research to collection and storage to display. This process seems to mirror the approach of the Old Masters, who were equally diligent in their attention to detail, from preparing the canvas to the final application of their artistry. A living example of conscientiousness is a Japanese guardian, Yuri, who guides her daughter Kaori to frame and paint her canvas of life.

In the lives of Yuri and Kaori, the museum visit is the fourth significant chapter of the day. The first chapter started with Yuri and Kaori choosing their clothes for an event at the White House [the official residence and workplace of the President of the United States, Washington, D.C.]. The attire had to be occasion-appropriate and weather-suitable, considering Kaori’s preference for long skirts and floral sweaters.

With her refreshing, self-reflecting facet, Yuri shares her appreciation for details: “Even in everyday life, we are aware of plate colours and food placement. I used to present tea ceremonies [Japanese ceremonial preparation and presentation of tea], which makes me conscious of the season and occasion. My grandmother, too, is conscious of seasons, presentations and order (she performed tea ceremonies, too).” This pared-down aesthetic is reflected in the duo’s movement—it whispers. Yuri must have read my mind: “In Japanese culture, you must tone down in public places; you don’t talk loudly.”

The museum is buzzing with loudness.

It would be a dream to have a silent atmosphere in the museum, minus distractions. However, unlike quiet classroom settings, museums often become loud with vain and vacant bragging parents, tantrum-throwing bored children, self-obsessed selfie-addicts, obnoxious loudcasters, clueless clowns, entitled loud senior citizens, and jostling “look at me” influencers (specialising in increasingly disfiguring artistic institutions).

Despite the crowd and clamour, it takes guardians like Yuri to retain her essence—move in silence while making a quiet space for Kaori. The mother-daughter duo’s imperceptible, nuanced dance offers glimpses of their thoughtfully executed strokes behind the composed demeanour and soft-hued attire. In this silent-moving classroom—of discovery, discussion and transformation, Yuri stewards Kaori’s character development.

An integral part of a museum experience is the unique space, emphasising atmospheric affects. The vast proportions and expansive galleries, with their neutral architectural spaces around large-scale art pieces, aid the museumgoer in appreciating details. The proportionally scaled, wood-panelled rooms at the NGA enable us to study the contrast of light and shadow, the emphasis on skin textures, and jewel detailing. Besides, the blending backgrounds spark interest in the dramatic effects of garment structures—billowing sleeves, intricate lace cuffs and precisely stretched upturned collars seen in the portraits by Dutch painters Frans Hals and Salomon de Bray. I remain especially in awe of the virtuoso brushwork depicting exquisitely portrayed embellishments—ruff collars—ruffled, changeable fabric worn around the neck.

Yuri explains: “You can only learn a little about a painting’s history by looking at the painting alone. I am describing (to Kaori) the origin of the paintings and the movement around the artworks. We first saw the Impressionists, then moved to the Dutch paintings, and they are different, which I want Kaori to notice. Even though Impressionists think a certain way, some also paint traditional paintings. By observing these paintings, Kaori can learn to express herself in different forms (if she wants).”

Individual opinions are encouraged and supported in Yuri and Kaori’s space. While Yuri prefers the presentation of natural light and visible brushstrokes of Impressionist artists like Degas, Monet and Cézanne, Kaori, age ten, shares her preference for Dutch paintings: “Portraits and landscapes (by Rembrandt and Hals) are more expressive and clear.”

By engaging with each other and encouraging Kaori to think and form opinions, Yuri is championing her daughter’s individualism and self-reliance. Refreshingly absent are theatrical cooing, cheerleading approval and infantilising. Instead, Yuri’s guidance is anchored in dignified self-assuredness.

Parenting is also about setting clear expectations: “I am a minimalist. The positive aspect of being a minimalist is considering where we place the item, whether it enhances what we already own, and whether it is easy to maintain. Kaori and her younger brother want more toys, which they can have, provided they tidy up.”

It is evident that fostering a sense of ownership positively impacts Kaori. Her enthusiasm made me eager to learn about Japanese schools. Kaori taught me that Japanese schools make learning fun, have dedicated swim time, encourage children to visit libraries independently, and welcome chores: “After lunch, we scrub the floors and clean the blackboards.” Then, with a hint of a smile, Kaori quickly added, “I like to keep my room tidy (unlike my messy brother).”

Kaori’s appreciation for the Japanese sense of independence—reinforced in school and society—is evident: “In Japan, children walk to school by themselves. It is safe. Our backpacks are equipped with buttons that double as alarms,” Kaori educates me on Japan’s high-quality public infrastructure (which she experienced on an extended visit to Japan). Stressing the importance of independence, Kaori informs me that she picked the fine restaurant (in Washington D.C.) where she and her mother lunched before the museum visit, further explaining that she also chose her dish. These details, though on the surface might appear negligible, are preparing Kaori for an adult life where she will face an onslaught of decision-making.

Structure is a mainstay in Kaori’s life. Akin to museum operations that unfold like clockwork, Kaori’s life mostly follows a schedule—piano practice, tennis classes and Japanese classes. And on Sunday, Kaori learns Mandarin at a Chinese school. This energy-packed young person has a healthy appetite—she wants to hike, visit adventure parks and partake in daily summer swims (and perhaps indulge in Anpan, a Japanese red bean sweet, on a visit to Japan). The museum will close doors for the day, clean and prepare the museum for the next day, and create quiet and calm for the artworks to rest and spaces to breathe. Kaori’s day echoes the winding down of NGA. On her return home, Kaori will write the closing pages of her last chapter. While Yuri prepares dinner, Kaori will practice the piano and watch a Japanese cartoon (If Kaori gets lucky, she might get a post-dinner green tea mochi!). As Kaori drifts into sleep, her mother’s guidance will be inscribed on her subconscious.

For this mother-daughter duo, cherishing time spent alone is as valuable as practising their culture imbued in independence. Under the quiet authority of her mother, Kaori learns to organise her life, progressing from child to adult, creating her authentic canvas. Like the transformative power of art, individuals like Yuri and Kaori are breathing cultural canvases from whom to learn and a testament to conscious giving, grateful receiving, and mindful living.