“Part of the garden’s enchantment

is following your nose and finding

those moments of awe.”

LOTTIE ALLEN

Head Gardener, Hidcote Manor Garden, UK

September 19, 2024

OPEN WINDOWS | In Conversation

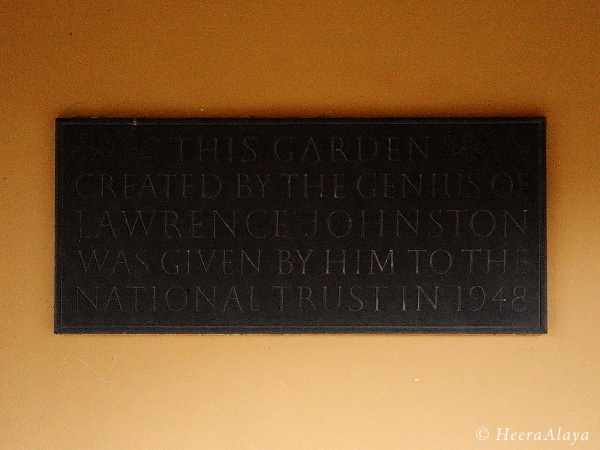

Passion and vision best encapsulate The late Major Lawrence Johnston’s (12 October 1871–27 April 1958) legacy. A garden designer and plantsman, Johnston designed Hidcote Manor Garden [Gloucestershire, England]—spread over 10.5 acres in the hamlet of Hidcote Bartrim—from 1907 to 1938. The National Trust [United Kingdom] that had recognised Johnston for Primula pulverulent [a pink rose] partnered with The Royal Horticultural Society [RHS]—of which Johnston was a fellow—to raise funds [since Johnston could not offer an endowment] acquiring the Hidcote Manor Garden in 1948. Recently, The National Trust, under the leadership of Head Gardener Lottie Allen, celebrated 75 glorious years of nurturing Hidcote Manor Garden—a cornucopia of glorious abundance, flushed with lushness and goodness, awash with colours and fragrances, and punctuated with melodic bird songs.

Heera Alaya: Were you interested in gardening as a child?

Lottie Allen: I wouldn’t say I was [interested in gardening]. I wanted to be outdoors and loved nature—the kind of native trees, insects, and wildlife that came with that. I was also a big bird watcher. But as far as horticulture is concerned, that wasn’t really on my mind initially. It was later in my teens onwards that I considered horticulture.

Did you start off studying horticulture in school and college?

I chose to do a degree in landscape management straight after A levels (I did geography, geology and art) and ultimately decided to work outdoors. After some work experience, I applied for and pursued a degree in landscape and amenity management [Writtle College]. At that time, I wanted to do more landscape contracting and construction. But as part of the degree, I went and worked at a National Trust garden in south Devon [South West England] and there I spent a year seeing the garden through, and I realised at that point that I wanted to see the effect of all the seasons in one garden.

Did you have to take up apprenticeships to further your interest?

No, my degree gave me a good grounding. The first year was what we could offer, from growing carrots in field locations to constructing a patio and plant identification. By the second year, there was more emphasis on where you found your interests. I was interested in Historic Gardens, so I studied those specifically. But having done this, after the second year, I did a working experience placement and spent a year in Colton [a village in Staffordshire, UK], which grounded me with my interest and passion.

You were also gardening on a rock in the middle of the sea?

That was the job before this one [at Hidcote Manor Garden]. I came to Hidcote from St Michael’s Mount [a tidal island in Mount’s Bay, Cornwall, England, UK ]. And yes, it is a rock in the middle of Mount’s Bay, the Western edge of West Cornwall. St Michael’s Mount has a different climate and plant collection. We are reliant on a lot of sun, which is also directly reflected from the sea, creating a micro-climate—that means there is no frost; we can grow a huge amount of succulents and exotic subtropical plants that you would struggle to grow in this country [United Kingdom] other than in places like St Michael’s Mount.

What did you have to consider before accepting your position at Hidcote Manor Garden?

Leaving the sea was quite a wrench; that is what I miss the most. The opportunity to work here at Hidcote, a garden of international significance and knowing I had to manage a team of 12 was a big part of the consideration. Besides, it means a lot to spend time helping to create and support the Conservation Management Plan—we were able to input into an existing written plan. The person writing it spent a lot of time with the garden team, working with what we already knew about the garden to create a baseline in one document.

Was it [the position of Head Gardener] daunting?

[Laughs] It was very daunting. Walking around the [Hidcote] garden with my shoulders high took me a while, and I felt like I had some reason for being here. But that came six months before the pandemic, so it’s been a learning process.

The [Hidcote] garden was closed during the pandemic.

Yes, we were closed (as in most places) by the end of March 2020 and reopened around June 2020. Those three months allowed me to work in the garden in a way I won’t have the time to do again. But it was also massively frustrating and unfortunate that many things were going on in the garden—the handkerchief tree [Davidia involucrata] was flowering its socks off, and there were all sorts of glimmers of hope that many people didn’t have the opportunity to see at that time. I look back with some fondness but also with a lot of sadness.

What is your approximate daily schedule as a Head Gardener?

It [schedule] is quite challenging to quantify. I spend some time on emails—just trying to catch up on what’s been happening. Then, it is a combination of formal meetings regarding what has been planned and informal catch-ups with the team, particularly the senior gardener team, regarding questions they might have or issues we need to address. If I am lucky, I am sometimes in the garden, but that’s becoming less and less. So, every week, I try to spend a day in the garden, but that can be as much decision-making as it is working in the garden.

As the Head Gardener at Hidcote, what specifically are you in charge of?

My job is more strategic in planning ahead for the team rather than day-to-day operations. The assistant head gardener plans and works through the weekly process of what we need to do. It is our job—mine and the assistant head gardener—to plan a bit further ahead and be aware of what’s coming next.

My job covers a whole range—from compliance to the health and safety side of things to visitor experience (what we want our visitors to come and enjoy and take away from the experience) to writing a guidebook. We have an author who is happy to write it, but that means a lot of input and how we want to see the finished article.

We are working on access work to make the garden much more accessible, which requires a lot of planning as this is a Grade 1 listed garden. It is not just a case of deciding whether we want to lift a slab and make it more levelled; many applications go into being allowed to modify the garden.

I have just come out of a senior gardeners meeting; I have two senior gardeners and an assistant head gardener, and they are the ones who lead day-to-day operations and know where they are at. Each gardener has different areas of the garden that they are leading, and there are other areas where we spend time depending on how much time is needed. The challenge is spending as much time as we need in those areas and moving on as quickly as possible to get to the next area (In Spring especially, weeds and flowers and everything grow simultaneously.).

Is Spring the busiest time of the year at Hidcote?

Yeah. We have a lot of plants coming out of the glass house. Everything is propagated and ready to go, and unless we get them in soon, they won’t hold up for display in the summer; they need to get in the ground and get going. We will lose the year if we miss planting by a month.

What time do gardeners start work?

Most of the team starts work at 8 O’clock; we get the first couple hours in the day before we have visitors. In certain situations, we close specific areas to work so we don’t have people trying to get past or ask questions (We are all pleased to answer questions, but there are times when visitors ask the same thing a dozen times and trying to get on with your job can be challenging.). We have a series of volunteers who function as garden guides; they can pick up questions, preempting some of the questions that might come our way.

What qualifications do your volunteers need compared to your full-time gardeners?

When interviewing volunteers, we examine their cultural knowledge and, more importantly, their ability to work as a team and follow instructions.

Somebody who’s well-trained isn’t necessarily what we are looking for because they would have come with other training, and each garden is managed differently. Volunteers need to be open and accepting, and whilst that might be how they did it in another place, this is how we do it here. It is much more about transferrable and personal skills than the horticultural skills. It is great if people come with some knowledge—what a weed is and what isn’t, but even here, we have a lot of self-seeding plants, some of which we like and encourage and others we would want to see as a weed. So, all of that knowledge has to be transferred.

Do you delegate tasks differently to volunteers and full-time gardeners?

Yes, tasks are delegated differently [to staff gardeners and volunteers]. We would have at least one staff member leading the group, if not a few people leading with them.

They [The beech trees] are stunning, just stunning. What makes these trees grow so tall?

The beech trees were planted simultaneously with another type of plant; it could have been larch [deciduous conifers] or similar trees. The idea was that they [previous landscape architects] wanted the beech trees to go straight up, so the concept of competition—the beech would win out; they were pushed to go higher. These beech trees [at Hidcote Garden] are over 100 years old. If you look at a beech tree growing in a field by itself, it will be much broader in girth and able to open itself out, whereas these [beech trees at Hidcote] have gone straight up and are all connected. And they probably wouldn’t have survived by themselves.

[We head to Allen’s upstairs office in the main building.]

There is a sprinkling—all over the garden—of tiny-dainty wildflowers in lilacs and pink, whites, powder blue, and salmon. Is it deliberate?

Many self-seeders are considered weeds in some gardens, while in others, they are considered plants. More often than not, they are plants in one part of the garden and weeds in another. So, we must be mindful of how those things work in our combinations to either come to fruition or pull them out because they are weeds in that place.

Your garden’s appeal is the profusion of layers, flowers, wildflowers, shrubs, grass and weeds. How do you get in between the rows without damaging the plants? You have to be like a nimble grasshopper!

[Laughs] My feet were never designed to be tiny feet that jump through the borders. We try to weed as much as possible before the garden is filled out—to get to places. Then, some delicate feet carefully weed, ensuring not to leave footprints and compressions. If you know what the plants are, you can work around things. And you can often find gardeners in the middle of the borders wondering how on earth they got there. But once you are on the ground, it’s much more open than you might think.

I observed your gardeners and volunteers working on the Red Borders, neatly laying protective sheets on the grass. What is the purpose of spreading protective sheets?

When they [gardeners and volunteers] come off the borders, they will have muck on their boots and themselves. The grass is as important as some plants, creating this foil for the garden. So if we damage the grass, we are almost ultimately damaging a plant in the border. So we keep it as protected as we can. It is not always possible, but that’s generally the intention.

It is the same practice for gravel paths as well. Allowing soil to get into the path doesn’t do any good. It means we start to get into the path and have to weed those. So, the tidier we can keep, the better.

I appreciate British orderliness. These details [mindfulness, presentation, standards] add to the overall aesthetics of the garden.

Yeah. It really does.

How do you prioritise, strategise and organise the entire garden?

We have a Garden Management Plan from the top level, which comes from the Conservation Management Plan. It’s about knowing how Johnston first created the garden and what he wanted from that space and then looking at how we can reflect that.

There are plants we can’t grow that he [Johnston] grew, so how do we create a similar feeling without specifically using the plants he used? So there is that whole thing in terms of what we are trying to achieve on a more annual basis.

And then, on a more weekly and monthly basis, to some extent, the seasonal tasks take care of themselves—for instance, we have schedules for plants that need pruning. January and February are pruning and then going down through the year.

I am about to go [after our conversation ] and look at the board for the week. We have a team of 12 and allocate people to what needs to be done over the week. We [the gardening team] get to it and think how we will fit all of this in a week, and most of the time, we achieve it. But sometimes, things get pushed to the following week. And that is just dependent on what we need to prioritise.

If we have some fairly significant visits and want the garden to look its absolute best, we might prioritise some of the weeding and make things look really good. However, there might be other times when we are more focused on putting plants in the ground and will return to weeding later.

Talking of pruning, I understand it is a legal offence [Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981] to harm nesting birds and eggs and that you can trim hedgerows only outside of bird-nesting months.

Yeah. We ensure we finish hedge cutting by the end of February at the latest because birds will start to create their nests or return to their nest by then, allowing them to breed and bring on the chicks. By the end of July, generally, most birds have fledged, and they are not using the hedges. We then start cutting the hedges in September.

There is far more behind picturesque, tranquil gardens. What parts of gardening are passion, art, science, and business?

It combines all of those [passion, art, science, and business]. On the business side, we need to ensure the garden looks at its best throughout the year to encourage year-round visitors, not just in Spring when the garden looks its best.

Scientifically, it is down to the plants and how they live and work in their given space. Some plants thrive in dry conditions, while others need more damp-moist conditions. Johnston was particularly keen on providing the right conditions so the plants would be their best rather than a weaker version, which we aim to provide.

Passion and the art of it [gardening] is very much down to the fact that we have no influence over what Johnston planted and planned. We have a lot of written word about how people felt when they came into the garden—when Johnston was planting it. And we can only interpret that and then layer a bit on top of it. Some plants have been grown in this garden since Johnston planted them, and there are others that we have added in the same atmosphere, evoking that emotion in that space in the best way. That is very much passion and art pulled together.

Do you work with botanical illustrations to plan colour combinations?

No, we don’t use botanical illustrations. Much of it involves testing and experimenting, which Johnston also did. But with the productive garden, we use spaces where we can plant in and out to see how they grow and what flowers and how they flower. Then, we use those flowers and see whether they are in the combinations we want, what the colours are, and if the tones are correct.

You are down to the tones!

Oh yeah, definitely. If you see the Red Borders, sometimes, certain tones work, and sometimes, they don’t. Hidcote is different; every garden is different, and plants will grow differently in each garden. Maybe not in terms of flower and colour, but certainly in terms of the actual habitat of the plant—it could grow well in one location, but on the top of a hill, north-facing might have a massive effect on how that plant grows.

Having planting areas to plant and see combinations we can grow together helps us decide on combinations and placements.

Do you have a seed bank, or do you source seeds?

The Old Orchard continues; they drop seeds, which we leave to sow and rake off margins. If we grow plants for the garden, we generally buy seeds, propagate them, and plant them in the garden.

How far ahead of time do you work on testing?

Two or three years, if not longer. It depends on, let’s say, if it’s an annual, then we would see what it looks like, “Yes, next year, that is what we want to grow.” And if it is more herbaceous perennials or shrubs, sometimes we would have seen it elsewhere and thought: ”That might work”, so we will bring that in. We often bring plants in, plant them and see what they do.

Do you take notes and document your findings?

Yes, to some extent, photos as well. We use a lot of photos to achieve what we have tried, what we have grown, and even the combinations—the seasonal plantings that we do are very much one-offs.

We feel we are at a peak, which you might never see at Hidcote again. The Head Gardeners spent some time at Giverny [Impressionist painter Claude Monet’s garden in Normandy, Northern France] last year and came back with quite a bit of inspiration about using the same colour—all oranges and yellows—and using them together rather than having a contrast.

Do you periodically seed the lawns?

Generally, no. Even if the lawns dry out and go yellow, they usually grow back.

How does your garden attract pollinators?

We are mindful of planting as many single flowers—very open single flowers, sunflowers, lilies, dahlias and the like—as we can because they are the best for pollinators.

Does Hidcote have hedgehogs [mammal] and other small creatures on the garden grounds?

We don’t have hedgehogs. We have badgers [omnivores], and badgers eat hedgehogs, so it is one or the other. In this situation, we cannot do anything about the badgers. We work alongside the badgers; they occasionally make a bit of a mess on our turf when looking for grubs, but generally, they keep to themselves.

There are rabbits and squirrels around. The grey squirrels can be a problem—they tend to chew the bark on the young trees, making it difficult to grow decent trees (we are still working on that).

What do nature-focused and sustainable gardening comprise?

It is being mindful about what we do and how we do it to incorporate as many habitats into the garden as possible. Where there were log piles, for instance, some beetles like shady log piles, and there are other things that like full sun—

Similar to lavender, which requires south-facing—

Yeah, exactly. It is being mindful of creating as many habitats as possible. For example, if there are water or wet ground areas, we might have some plants that thrive in them, and as a result, those flowers are great for certain insects. And certainly not destroy the habitats that we know are being used. We have orchards, long grass, and short grass; all these different things offer other types of insects or beings in those habitats.

The garden site (to the far end) has piles of stacked chopped wood.

There was a time when we had a lot of logs, and we started to create bales. We burn some of the logs for the log burner for the volunteer shed when they have breaks, but the rest is for beasts and bugs.

Can you tell me about the irrigation system at Hidcote?

At Hidcote, we use as little water as possible, and when we do, it is water harvested from a natural spring running through the garden. This year [2024], we hardly used any of it [water from the tanks]. But we would irrigate the main lawn if we needed to. The central access, the main strip [Great Lawn], is the most important, as the grass is as important as the plants and needs to be kept green. Whereas the big lawn, if that goes yellow, it is just dealing with the hot weather and it would come back.

What is the manure source?

We have a composite area. We collect everything—grass, deadheads, weeds—and put them into a bay. We bring wood chips and branches that we throw into a wood chipper. We mix the two, creating the compost we put in the garden.

Do you use pesticides?

We use a small amount of pesticides, mainly in large areas where we don’t have the time to grapple and weed. Hopefully, we will eventually stop using pesticides.

Since taking over as Head Gardener, have you been able to introduce anything new to the garden site?

Our biggest project is the Pillar Garden, which has a series of upright columns. They were huge and taking up space, so we cut them back to trunks and allowed them to grow back to where they were. It is a big project that we managed to complete.

Other than that, the plant shelter, which had a roof and was closed until the winter, has been taken down and replaced with a new space.

Do gardens naturally change over time?

I hope that if Johnston were ever to visit—he passed away in 1958—he would recognise the garden because a lot of it is very similar to how he laid it out. Certainly, the structure, the hedges, the viewpoints, and the soft plantings inside the rooms are different, but hopefully, most of that is similar in terms of its feeling and looks, even if it is not the same plant.

What can we learn from the late Major Lawrence Johnston’s vision and passion?

[We can learn] To be bold and not fear mistakes. On a couple of occasions, we know Johnston laid something out, and then within a few years, he changed it and did something different. I don’t think gardening is subtle. You are instigating something with the act of planting. So don’t fear that you will get it wrong; be bold and plant combinations.

What is a good route for aspirants to take in the field of horticulture?

It’s important not to be constrained to one garden and to take opportunities in the apprenticeship route that allow you to work and learn, experience different gardens, see spaces, and be inspired.

What has been the most satisfying aspect during your tenure at Hidcote?

The garden team—they are a brilliant bunch. We have undergone several changes with COVID, but they are passionate about the garden, understand where we are trying to go with it and support what is going forward. They [the garden team] will have their own identities and feelings on how things come to be. They are all highly skilled individuals, making it a pleasure to work with them.

What can visitors look forward to in the Spring of 2025?

The Pillar Garden is starting to take shape, and we are beginning to work on the colour combinations. So this year [2024] is a trial year, and next year, the garden will look spectacular. Upstream, there is a lot of work with marginal plants, which will look fantastic.

How does the winter make the garden unique?

By that time (winter), the hedges are cut, and you can see crisp and sharp angles. The views that are otherwise swamped and covered with plants are clear, allowing you to better understand the garden’s structure and form. We want visitors to return for more than one season, which is good for our business.

What do you want your visitors to experience at Hidcote?

The experience is different for different people and also different per garden space. Each of the garden rooms makes you feel differently. Walking into the White Garden makes you feel calm and serene. Then, when you go to Mrs Winthrop’s Garden, which is blue and yellow, you feel lively and energetic. So, the experience is different in different spaces.

I am in love with Hidcote and am considering turning into an adventurous butterfly—

[Laughs] And fly around.

[I beam] Yes, glide through dainty wildflowers, pause to a singing Blackbird, take a dip in the bathing pool, bounce in the wilderness with bumble bees, float up toward the glorious beech trees and continue not knowing what I would discover around the corner, which was Major Johnston’s intention—not to have a single vista but to be met with surprises at every turn.

Yeah, exploration and discovery are big parts of Hidcote. Often, people come and want a map—they want to know they have been everywhere and done everything, but part of the garden’s enchantment is following your nose and finding those moments of awe. As you turn a corner, it is something different you didn’t expect, giving you moments of joy.

Learn more about Hidcote Garden and The National Trust.